Angular Services, providedIn and Lazy Modules

I often see people confused about how the DI works, in particular with lazy loaded modules. In this article we’re going to explore some dependency injection particularities with Angular, specifically in combination with lazy loaded modules.

Angular always had a dependency injection support, from Angular.js v1.x to the new, rewritten Angular 2+. There are a couple ways of registering services in Angular, which might have an impact on the lifecycle of the service itself as well as to tree shaking and bundle size. Let’s dive in.

Wanna try it out by yourself. Here’s an example repository: https://github.com/juristr/angular-services-di-lazyloading

Let’s assume we have the following example application.

src

|___ data-access

|__ data.service.ts

|__ ...

|__ data-access.module.ts

|___ feature1

|__ ...

|__ feature1.module.ts

|___ feature2

|__ ...

|__ feature2.module.tsRegistering the service on the providers array

The classic/standard approach of registering services (especially pre-Angular v8) is to register it on the NgModule.providers array.

import { DataService } from './data.service'

...

@NgModule({

...

providers: [ DataService ]

})

export class DataAccessModule { }No Provider for DataService error

Assume you need the DataService inside a component that is part of Feature1Module. Naively you would simply add it to the constructor and expect the dependency injector to properly provide it:

import { DataService } from '../data-access/data.service';

...

@Component({

selector: '',

...

})

export class Feature1Component {

constructor(private dataService: DataService) {}

}However, you might get this error:

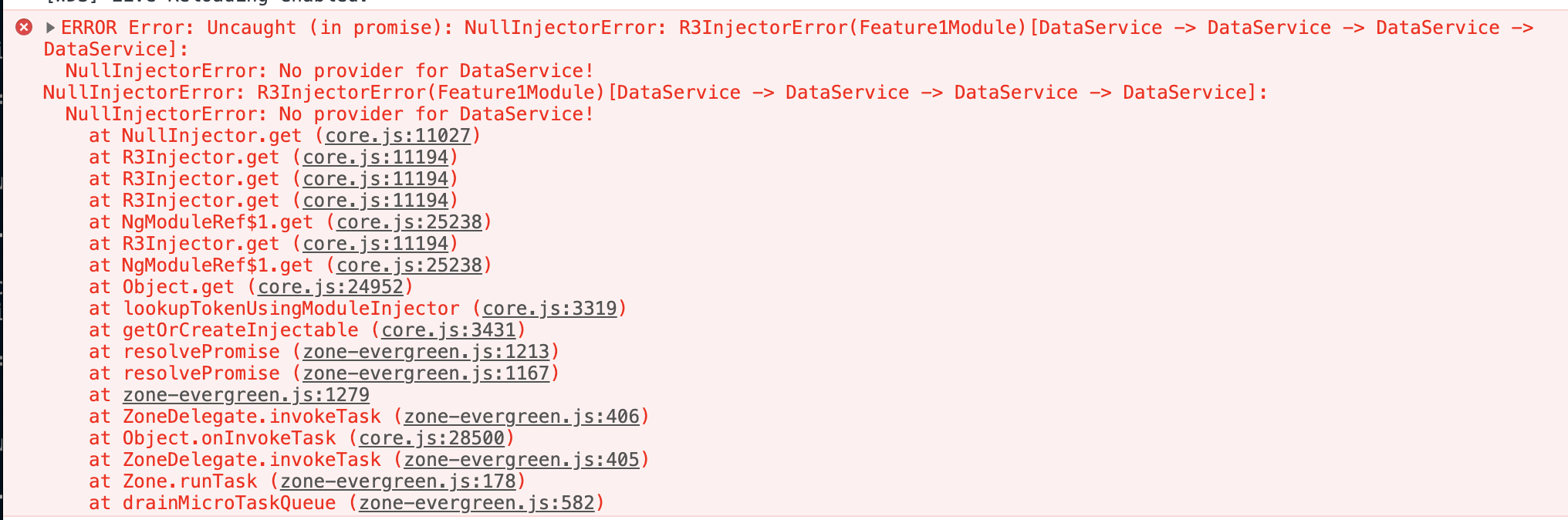

This happens because we registered the DataService on the DataAccessModule.provider array. Since we also didn’t import the DataAccessModule into the Feature1Module.imports array, Feature1Module does not know about the existence of the DataService.

Note: this error might not be bad at all. Assume that service is accessing some underlying NgrxStore, which in turn registers its effects and reducers on the

DataAccessModule. You’d definitely wantFeature1Moduleto importDataAccessModuleto get all that Ngrx infrastructure registered and set up.

❌ Don’t register the service on other NgModules

Now obviously what you could do to circumvent the before mentioned error, is to register the DataService directly on the Feature1Module.providers array.

// don't import services from other modules and register them here

import { DataService } from '../data-access/data.service';

...

@NgModule({

...

providers: [DataService] // <<<

})

export class Feature1Module {}This should absolutely be avoided! Angular modules have most often a 1-1 correspondence with some file system folder. The Angular service should thus be registered on the NgModule that is located closest to where the service file is. In our case, you’d register the DataService on the DataAccessModule.provider located in the src/data-access/data-access.module.ts.

Runtime situation

When you search for Angular injectors you’ll most probably came across the hierarchical nature of injectors in Angular. There’s basically a NgModule injector (ModuleInjector) and an element level injector (ElementInjector) scoped to DOM elements and used by Directives or Components. You can read more on the official docs here.

Those things are important and useful for scoping Angular services in their visibility and lifetime. In our specific example there’s another mechanism that kicks in though.

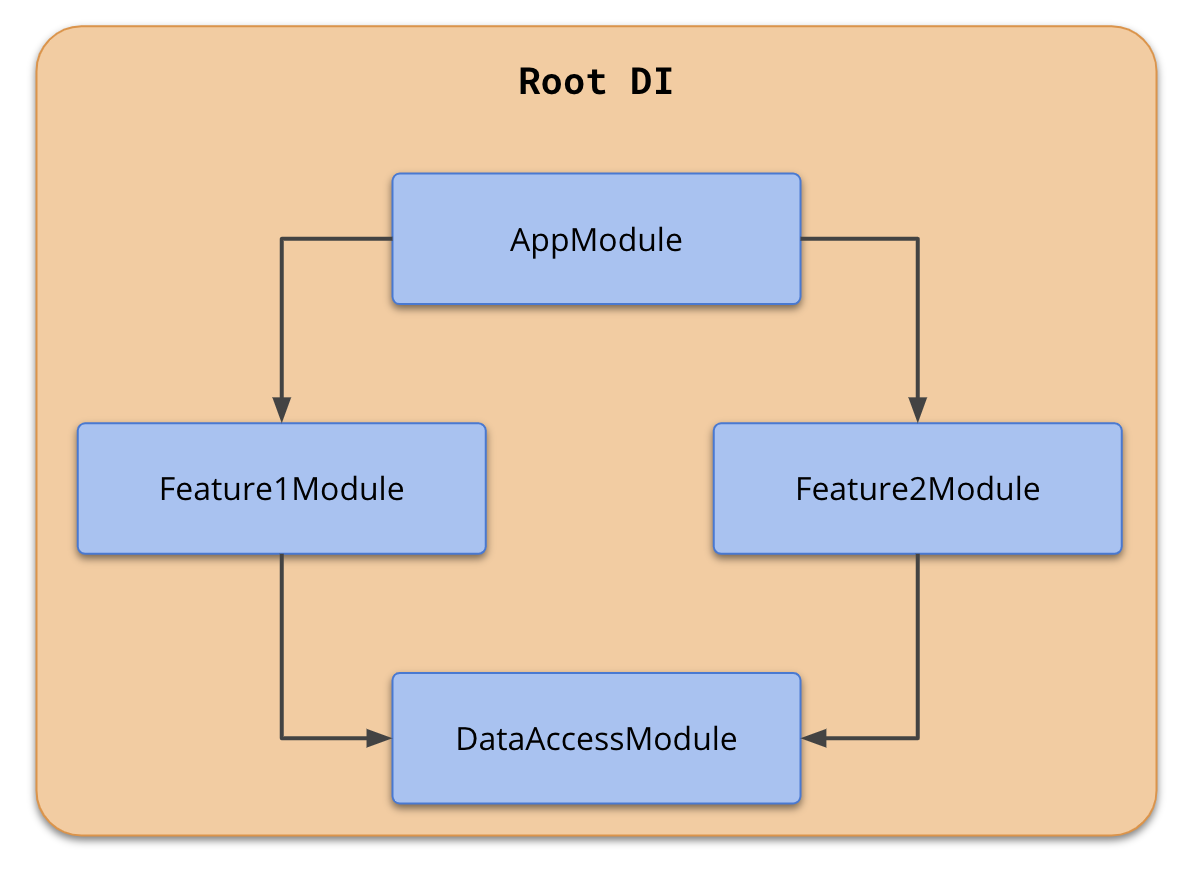

Angular services are globally available on the dependency injector by default or to be more specific, for eagerly loaded modules. What do I mean?

Reusing our previous example, once Feature1Module imports DataAccessModule, the DataService is registered on the root injector and globally available. Meaning if Feature2Module requires DataService it’ll work without exception, even though Feature2Module did not import DataAccessModule (where DataService is registered). I do not recommend relying on that though!

You should not rely on that because once you decide to lazy load modules you might run into trouble.

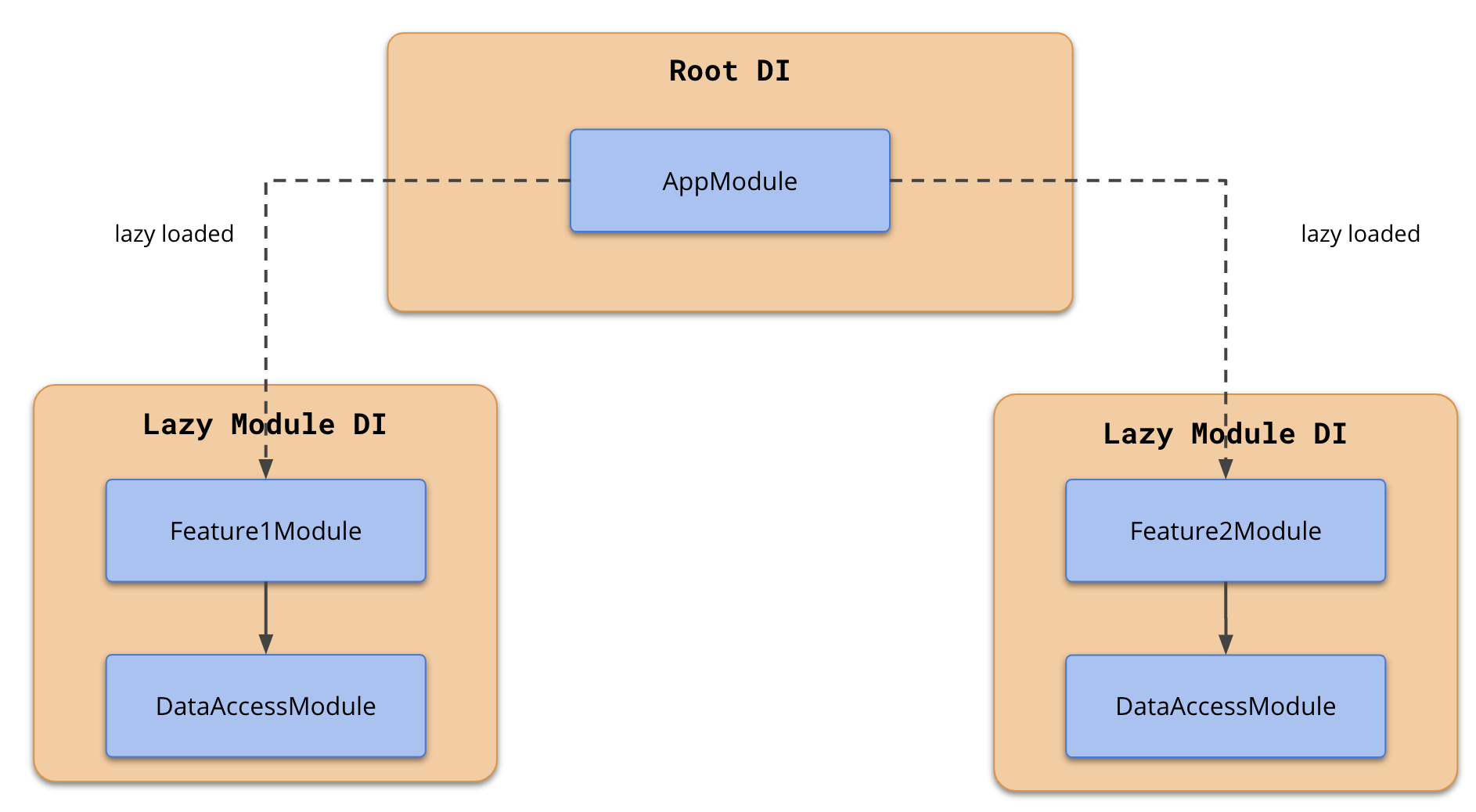

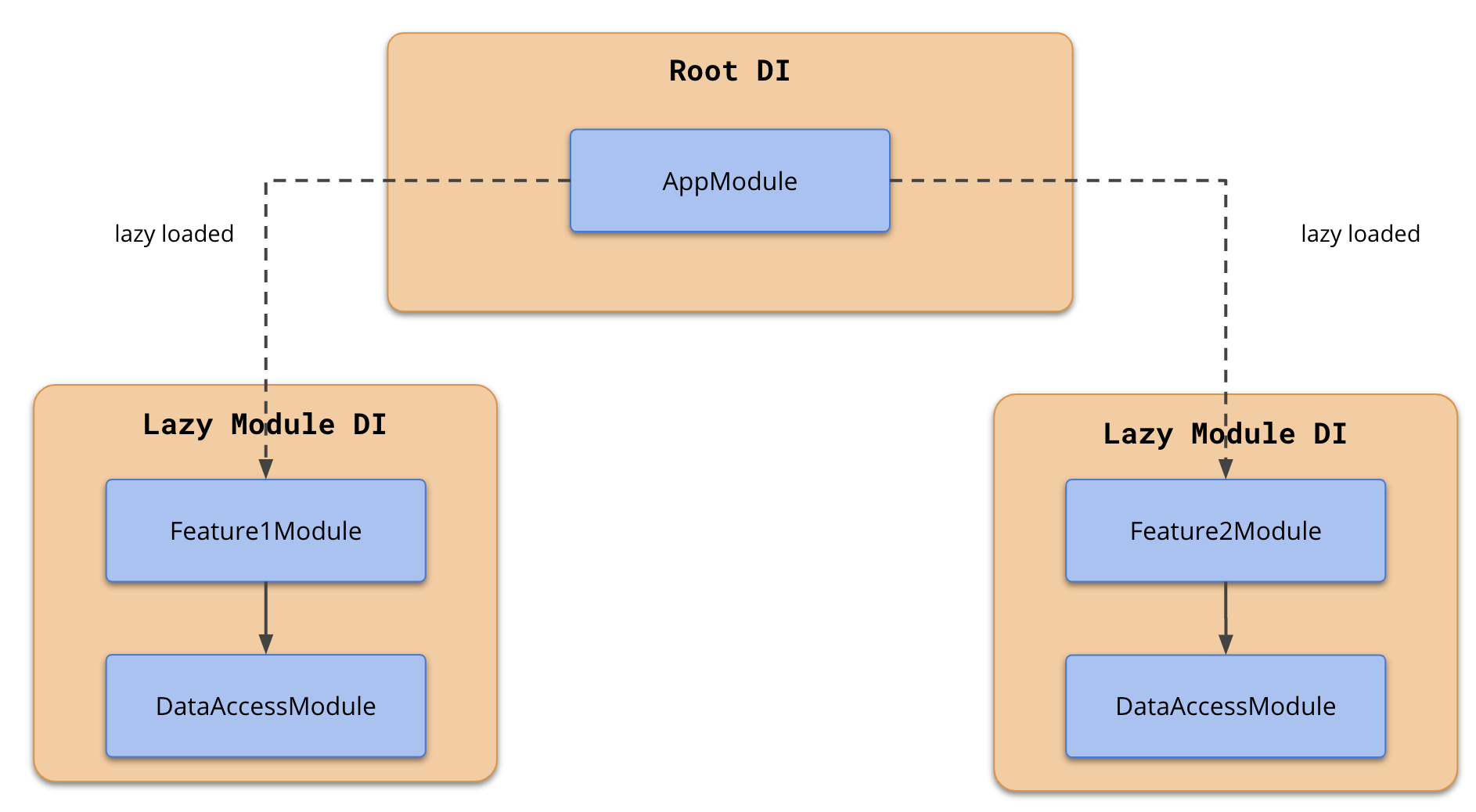

When the Angular router lazy-loads a module, it creates a new injector. This injector is a child of the root application injector. Imagine a tree of injectors; there is a single root injector and then a child injector for each lazy loaded module. The router adds all of the providers from the root injector to the child injector. When the router creates a component within the lazy-loaded context, Angular prefers service instances created from these providers to the service instances of the application root injector.

Source: https://angular.io/guide/providers#limiting-provider-scope-by-lazy-loading-modules

Basically the situation looks as follows:

As mentioned, you should import the DataAccessModule wherever you need access to the DataService. In our example that would mean to import it into the Feature1Module and Feature2Module.

So far so good, but what happens if we decide to lazy load both of the feature modules?

Since both of them import the DataAccessModule the DataService on the providers array gets registered to the created child injector for each of the two lazy loaded feature modules. Hence we end up with 2 instances at runtime. This might not be a problem but definitely should be considered, especially if the services are stateful.

Bundling situation

What does that mean at build time? Since the commonChunk is enabled by default, we’d get the following bundles if we lazy load both feature modules:

feature1-feature1-module.js- contains all feature1 related codefeature2-feature2-module.js- contains all feature2 related codecommon.js- contains shared code among the two, e.g. ourDataAccessModuleandDataService

Using the providedIn syntax

Angular v8 introduced the providedIn syntax. Let’s see how that changes the situation. The providedIn option on the Injectable() can be used with root or by providing the according NgModule.

Example 1: registering a service on the root injector

@Injectable({

providedIn: 'root',

})

export class DataService {...}Example 2: registering a service on module injector

@Injectable({

providedIn: DataAccessModule,

})

export class DataService {...}Runtime situation

Using a setup as shown in example 2 leads to two services being live at runtime, one for each lazy loaded feature. This is similar to using the providers array, but with the benefit of being able to leverage tree-shaking and thus potentially a reduced bundle size (see the bundling section later).

As a side-note: most of the time services are registered as

providedIn: 'root'or if you need more control over the instance, directly on the actual@Component({ providers: [... ]}).

If you use

providedIn: DataAccessModuleyou need to be aware of potential circular dependencies. Why? Well, we know that we need to register Components on anNgModule(at least as of now). IfDataAccessModulehas a componentDetailViewComponentwhich is registered on theDataAccessModuleand also importsDataService, we have a circular dependency:DetailViewComponent -> DataService -> DataAccessModule -> DetailViewComponent. There are ways around that, but for simplicity I would fallback to the NgModule.providers registration at that point.

With the providedIn: 'root' method, once the lazy loaded chunk containing the service has been registered, it’ll be registered at the app’s root injector and thus there will only be one global singleton instance. Whenever another module also referencing the service gets loaded, it’ll receive the same instance of the service from the dependency injector. This even holds for lazy loaded Angular modules.

Example

Assume the user navigates to /feature1 which triggers the lazy loading of Feature1Module and the corresponding Feature1Component. The latter requires an instance of a DataService that gets loaded and since it doesn’t exist on the dependency injector yet, it gets registered.

Then the user navigates to feature2 which again triggers the lazy loading of Feature2Module and the corresponding Feature2Component. Again, the latter requires an instance of the DataService which at this point already exists globally and thus the in-memory instance will be returned.

Bundling situation

When using the providedIn syntax, the bundling situation depends on how things are referenced.

Option 1: Feature Modules reference DataAccessModule

If Feature1Module and Feature2Module also reference the DataAccessModule in it’s imports array, then the bundling situation is exactly the same as described before. We’d get a common.js containing both, the DataAccessModule and DataService.

Option 2: Feature Modules just reference the DataService, but not DataAccessModule

We’ve learned that the providedIn syntax auto-registers the service on a first usage basis. Thus, if Feature1Module and Feature2Module don’t need any logic on the DataAccessModule other than the actual DataService, there’s no need to import the DataAccessModule into their corresponding NgModule.imports section. As a result, the DataAccessModule would never be referenced anywhere and thus not get bundled into the common.js chunk.

Option 3: Feature Modules reference the DataAccessModule, but no one the DataService

Assume for some reason the DataService is not used by both, the Feature1Module and Feature2Module .

In the case where the DataAccessModule references the DataService in it’s providers array, the DataService would still be bundled into the common.js. If the DataService however uses the providedIn syntax, it would be tree-shaken out and not finish in any bundle. This happens regardless whether we pass root or the NgModule reference to the providedIn property.

Thoughts about NgRx

When you’re using an NgRx Store for your data management (and this holds probably for other state management solutions as well), there is some logic you’ll have in your AppModule as well as your feature modules. For example:

// feature1.module.ts

@NgModule({

...

imports: [

StoreModule.forFeature(

fromFeature.FEATURE1_KEY,

fromFeature.feature1Reducer

),

EffectsModule.forFeature([Feature1Effects])

]

})

export class Feature1Module {}Now assume you use the Facade pattern. That would be an Angular service that could easily use the providedIn syntax. As a result, some user might import the Feature1Facade into some other modules, without importing Feature1Module. However, you need to make sure that the NgRx registration logic in Feature1Module has been executed before, otherwise you might run into a runtime exception where you access Feature1Facade which tries to access some NgRx store data which hasn’t been initialized though.

How to solve that? It depends on your architecture setup. You could have a setup where the NgRx setup is always part of the main feature module of your domain, and thus all other lazy loaded modules of that specific domain can rely on the NgRx part to be initialized already. Alternatively, don’t use the providedIn syntax and force developers to import the according Feature1Module whenever they want to use that part of the NgRx store.

I’m curious what your thoughts are, so feel free to ping me :smiley:.

Conclusion

So we’ve seen

- different ways of registering Angular services

- the runtime impact of using the

providedInorNgModule.providersregistration (e.g. with the number of instances at runtime for lazy loaded modules) - the bundling impact, in that

providedInallows to tree-shake out Angular services that are not being used.

So in general I always recommend the providedIn to use as the default. You can then fallback to the NgModule.providers registration or even to the Component level registration if you have a valid reason to do so.